Layered protocols

We just saw a very simple example of compositional testing of a peer-to-peer interface. It’s also possible to use compositional testing at the interface between layers in a layered protocol stack.

As an example, let’s look at the very simple leader election protocol, introduced in this paper in 1979.

In this protocol we have a collection of distributed processes

organized in a ring. Each process can send messages to its right

neighbor in the ring and receive message from left neighbor. A process

has a unique id drawn from some totally ordered set (say, the

integers). The purpose of the protocol is to discover which process

has the highest id value. This process is elected as the “leader”.

This protocol itself is trivially simple. Each process transmits its

own id value. When it receives a value, it retransmits the value,

but only if it is greater than the process’ own id value. If a

process receives its own id, this value must have traveled all the

way around the ring, so the process knows its id is greater than all

others and it declares itself leader.

Interface specifications

We’ll start with a service specification for this protocol:

object asgn = {

function pid(X:node.t) : id.t

axiom [injectivity] pid(X) = pid(Y) -> X = Y

}

object serv = {

action elect(v:node.t)

object spec = {

before elect {

assert asgn.pid(v) >= asgn.pid(X)

}

}

}

The abstract type node.t represents a reference to a process in our

system (for example, its network address). The asgn object defines

an assignment of id values to nodes, represented by the function

pid. The fact that the id values are unique is guaranteed by the

axiom injectivity.

The service specification serv defines one action elect which is

called when a given node is elected leader. Its specification says

that only the node with the maximum id value can be elected.

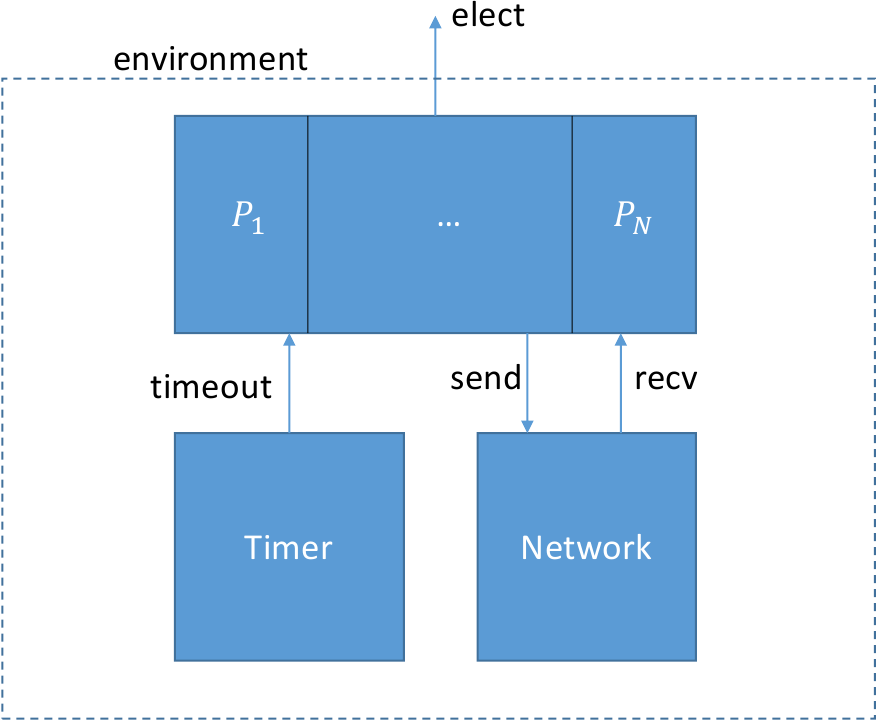

Our protocol consists of a collection of concurrent process layered on top of two services: a network service and a timer service:

Let’s consider now the two intermediate interfaces. The specification for the network service is quite simple and comes from IVy’s standard library:

module ip_simple(addr,pkt) = {

import action recv(dst:addr,v:pkt)

export action send(src:addr,dst:addr,v:pkt)

object spec = {

relation sent(V:pkt, N:addr)

after init {

sent(V, N) := false

}

before send {

sent(v,dst) := true

}

before recv {

assert sent(v,dst)

}

}

}

The interface is a module with two parameters: the type addr of

network addresses, and the type pkt of packets. It has two actions,

recv and send. The relation sent tells us which values have been sent to which

nodes. Initially, nothing has been sent. The interface provides two

actions send and recv which are called, respectively, when a value

is sent or received. The src and dst parameters respectively give the source

and desitination addresses of the packets.

The specification says that a value is marked as sent when send

occurs and a value must be marked sent before it can be received.

This describes a network service that can duplicate or re-order

messages, but cannot corrupt messages.

The specification of the timer service is also quite simple and comes from the standard libarary:

module timeout_sec = {

import action timeout

}

The timer service simply calls timeout from time to time, with no

specification as to when.

Protocol implementation

Now that we have the specificaitons of all the interfaces, let’s define the protocol itself:

instance net : ip_simple(node.t,id.t)

instance timer(X:node.t) : timeout_sec

object proto = {

implement timer.timeout(me:node.t) = {

call trans.send(node.next(me),asgn.pid(me))

}

implement net.recv(me:node.t,v:id.t) {

if v = asgn.pid(me) { # Found a leader!

call serv.elect(me)

}

else if v > asgn.pid(me) { # pass message to next node

call trans.send(node.next(me),v)

}

}

}

We create one instance of the network module, and one timer for each

node. The protocol implements the interface actions timer.timeout

and net.recv. When a node times out, it transmits the node’s id to

the next process in the ring, defined by the the action

node.next (which we’ll define shortly).

When a node receives an id value v, it checks whether v

is its own id according to the id assignment asgn. If so, the

process knows it is leader and calls serv.elect. Otherwise, if the

received value is greater, it calls net.send to send the value on to

the next node in the ring.

With our protocol implemented, we still need to provide concrete types

for node and id. If we were formally verifying the protocol, we

would probably treat these as abstract datatypes with specified

mathematical properties. For testing, though, we just need some

concrete types. Here is one possiblity:

object node = {

type t

interpret t -> bv[1]

action next(x:t) returns (y:t) = {

y := x + 1

}

}

object id = {

type t

interpret t -> bv[8]

}

That is, node addresses are one-bit binary numbers (meaning we have just two nodes, and id’s are 8-bit numbers. Often it’s a good idea to start testing with small datatypes. In the case of the leader election ring, more nodes would increase the amount of time needed to see an election event.

Compositionally testing the leader election protocol

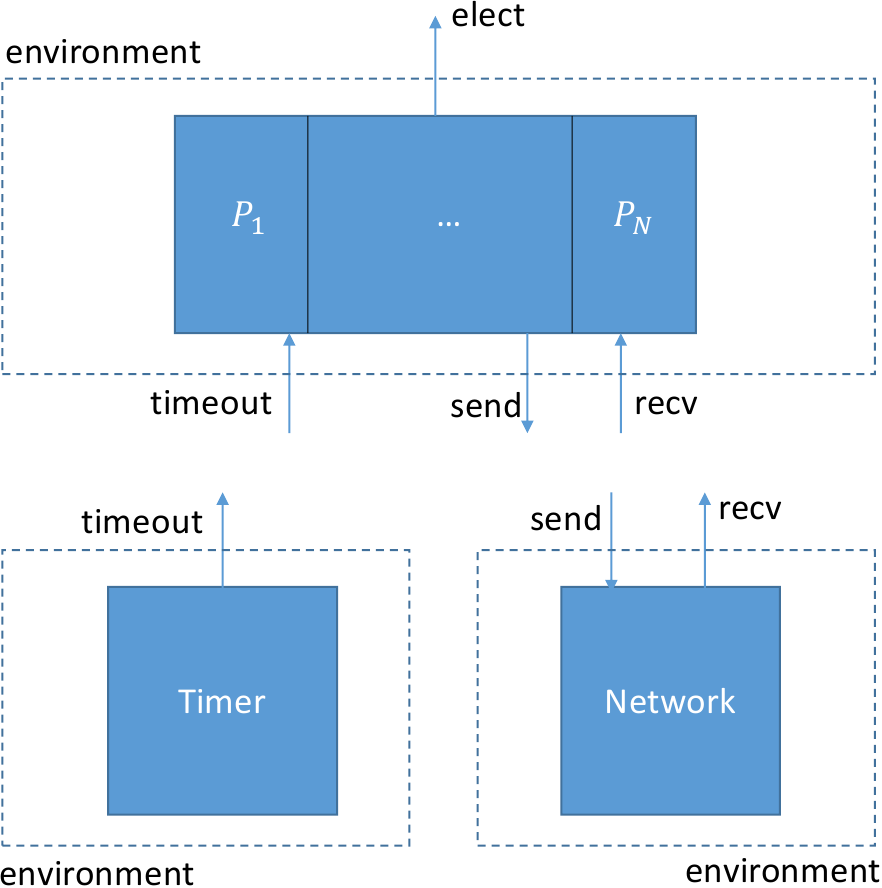

We’re going to divide the system into three isolates, one for each of its major components. Here is what the three isolates will look like:

Here are the isolate definitions:

trusted isolate iso_p = proto with serv,node,id,asgn,net,timer

trusted isolate iso_t = timer

trusted isolate iso_n = net with node,id

We added the keyword trusted to these isolates to indicate to IVy

that they will be verified informally by testing. Notice that the

isolate for proto contains its service specification as well as the

specifications of all of the other components. We need to test that

proto lives up to its guarantees at all of its interfaces, provided

that all of its assumptions hold. On the other hand, net needs only

the specifications of node and id (the net object contains its

own service specification).

We can now use IVy to compile test environments for each of the isolates, based on the interface specifications. Let’s start with the high-level protocol:

$ ivy_to_cpp isolate=iso_p target=test build=true leader_election_ring.ivy

g++ -I $Z3DIR/include -L $Z3DIR/lib -g -o leader_election_ring leader_election_ring.cpp -lz3

We run the tester:

$ ./leader_election_ring

> timer.timeout(1)

< net.send(1,0,170)

> net.recv(0,170)

< net.send(0,1,170)

> net.recv(0,170)

< net.send(0,1,170)

> net.recv(0,170)

< net.send(0,1,170)

> timer.timeout(0)

< net.send(0,1,149)

> timer.timeout(0)

< net.send(0,1,149)

> timer.timeout(0)

< net.send(0,1,149)

> net.recv(0,170)

...

> net.recv(0,170)

< net.send(0,1,170)

> timer.timeout(0)

< net.send(0,1,149)

> net.recv(1,170)

< serv.elect(1)

In this run, process 1 times out and sends its id 170 to process

- Process 0 receives this id and forwards it back to process 1 (meaning process 0’s id must be less than 170). Later, process 0 times out and sends its id 149 to process 1. Eventually, the network decides to deliver to process 1 the message with its own id, causing process 1 to be elected. When this happens, the assertion monitor checkes that in fact process 1 has the highest id.

The important point here is that there is no actual network. The

tester is simulating the network by randomly selecting actions

consistent with the history of actions at the interface. In practice,

this means that the tester stores the relation sent (the state of

the network interface specification) and only calls net.recv with

packets that have been previously sent. When there are multiple

choices, the tester makes an effort to select uniformly. This is a

hard problem in general, however. In practice the distribution will be

non-uniform. If you look at the calls to net.recv, you can see that

there is some duplication of sent packets, as we would expect.

We can see here a major advantage of compositional testing over integration testing. If we used a real network to test our protocol, we might have to wait a long time for a packet duplication to occur (in fact, this might never occur unless we take care to stress the network appropriately). The resilience of our protocol to packet duplication would not be well tested, as it is here. Similarly, our protocol might have unintended dependences on timing. Since timeout events are being generated randomly here, and not based on wall clock time, we can see timings that might occur rarely in the actual system, perhaps only under very heavy load.

Now let’s turn to the network isolate. We compile and run:

$ ivy_to_cpp isolate=iso_n target=test build=true leader_election_ring.ivy

g++ -I $Z3DIR/include -L $Z3DIR/lib -g -o leader_election_ring leader_election_ring.cpp -lz3

./leader_election_ring

> net.send(0,0,168)

< net.recv(0,168)

> net.send(0,0,243)

< net.recv(0,243)

> net.send(0,0,13)

< net.recv(0,13)

> net.send(1,0,108)

> net.send(0,0,84)

> net.send(0,0,78)

< net.recv(0,108)

< net.recv(0,84)

< net.recv(0,78)

> net.send(1,0,17)

< net.recv(0,17)

> net.send(0,1,167)

< net.recv(1,167)

> net.send(1,0,3)

> net.send(0,1,13)

...

The object net is actually just a wrapper around the operating

system’s networking API. Therefore, when we test net, we are

actually testing the operating system’s networking stack. Fortunately,

testing reveals no errors. Notice though, that the tester is

generating a wider variety of packets than the protocol could

actually generate. In fact, it’s simply generating packet values

uniformly at random. In this sense, the network stack is also being

better tested than it would be if composed with the actual protocol.

Finally, we can test the timer:

$ ivy_to_cpp isolate=iso_t target=test build=true leader_election_ring.ivy

g++ -I $Z3DIR/include -L $Z3DIR/lib -g -o leader_election_ring leader_election_ring.cpp -lz3

./leader_election_ring

< timer.timeout(0)

< timer.timeout(1)

< timer.timeout(0)

< timer.timeout(1)

< timer.timeout(0)

< timer.timeout(1)

< timer.timeout(0)

< timer.timeout(1)

< timer.timeout(0)

...

Not very interesting, but it shows both timeouts occurring once every second, which is what we expect. Again, we are really testing the operating system here (and also IVy’s run time scheduler, which uses the operating system API).

Running the protocol

Now that we’ve tested the components, we can compile the whole system

and run it as a collection of independent processes. Our protocol is an

example of a parameterized object. Ivy can decompose it

into a collection of processes based on the parameter me. Each

value of the parameter becomes an individual process. This

transformation is called parameter stripping.

To do this, we use the following declaration:

extract iso_impl(me:node.t) = proto(me),net(me),timer(me),node,id,asgn

This describes a special kind of isolate called an extract. Extracts

are intended to be run in production and don’t include the

specification monitors. In the extract declaration, me is a symbolic

constant that represents the first parameter of of each action and

state component in the object. This parameter is “stripped” by

replacing it with the symbolic constant me.

Before thinking about this too hard, let’s just run it to see what

happens. We compile as usual, with one difference: we use the option

target=repl. Instead of generating a test environment, IVy provides

a read-eval-print loop as the environment:

$ ivy_to_cpp target=repl isolate=iso_impl build=true leader_election_ring.ivy

g++ -I $Z3DIR/include -L $Z3DIR/lib -g -o leader_election_ring leader_election_ring.cpp -lz3

This produces an executable that takes one parameter me on the

command line. Let’s create two terminals A and B to run process 0 and

process 1 respectively:

A: $ ./leader_election_ring 0

A: >

B: $ ./leader_election_ring 1

B: >

A: < serve.elect

A: < serve.elect

A: < serve.elect

...

Notice that nothing happens when we start node 0. It is sending packets once per second, but they are being dropped because no port is yet open to receive them. After we start node 1, it forwards node 0’s packets, which causes node 0 to be elected (and to continues to be elected once per second).